After my middle school zoom lesson ends, I send the students off, saying “go get some movement in and get off the screens! I’ll see you tomorrow.” The kids linger and argue that they don’t need to go because they plan to sit at their laptops whether they have zoom open or not. They explain patiently that they plan to play games or watch videos until their next zoom starts anyway, so why should they leave their friends during that time?

During our zooms, many more cameras are off than there are children uncomfortable with cameras, and I’ve learned to recognize the difference in lag times when I ask a question and kids answer: there is the “I’m using my trackpad to unmute,” the several seconds longer of “I’m doing something else and need to catch up before unmuting.” and the non-response of “I’ve put you on mute so I can play a game.” I have received more than one parent email informing me their child puts the lesson on mute in order to watch Youtube or Tiktok.

Parents express worries about how much time their children spend on screens due to virtual instruction, and many schools provide guidelines for teachers to minimize the time students spend on screens. We are encouraged to find ways to reduce required screen time for children.

The overall challenge we face is maintaining healthy behaviors in an environment in which digital media is an essential part of education and life. These healthy behaviors can be summarized in the phrase digital well-being, which “refers to the (lack) of balance that we may experience in relation to mobile connectivity” (Vanden Abeele, 2020).

I suspect that the children I teach who use digital devices excessively do not do so due to increased demands for on-device time from their teachers. Rather, it is the product of increased access, decreased supervision, and decreased opportunities for movement and activity away from devices.

Prior to remote learning, students had relatively minimal screen time during the school day even when some course work required computer and device usage. Passing time, transitions in class, lunch, recess, school sports, and required PE courses meant that children were active and off of their devices for significant portions of their day. During remote crisis learning, even “off screen” tasks, like writing in student planners, require screen time, and all of the incidental activity opportunities of being in a school building have disappeared.

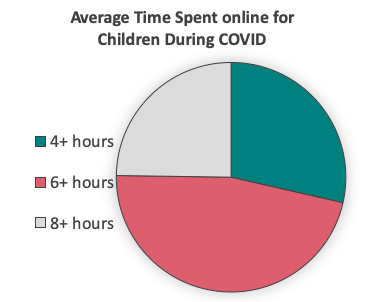

My experience is reflected in research. A ParentsTogether survey of 3,000 families found a 500% increase in screen time for children during the pandemic (ParentsTogether, 2020). The apps used are not necessarily educational: “YouTube (78.21%), Netflix (49.64%), and TikTok (33.41%)” (ParentsTogether, 2020). The survey further found that, though 4% of students spent more than 8 hours online before remote learning, now that number is 26% (Parents Together,2020), and 30% of those children are spending at least 4 hours unsupervised (Parents Together, 2020). Compare this to at 2016 report from the American Academy of Pediatrics that reports an average of 2 hours of screen time for children per day (AAP, 2016).

The AAP does not suggest a specific limit to digital media for children ages 8-17 as long as it doesn’t interfere with physical activity or sleep, so this behavior does not necessarily raise red flags for children’s health in itself (AAP, 2016). Specifically, the AAP recommends 8-12 hours of sleep, 1 hour of vigorous physical activity per day “media-free times. . .and media-free zones,” saying “children should not sleep with devices in their bedrooms, including TVs, computers, and smartphones” (AAP, 2016).

Though, this increase in digital device use is not the cause of the decrease in movement, it coincides with it and increased time on these devices prevents the replacement of the activity lost due to the cessation of in-building learning with other forms of movement. Further, increased use of devices has an adverse effect on sleep patterns and the need for multiple users to be online live within households has driven devices into children’s bedrooms. It is a trifecta of conditions that discourage healthy limits to device use and encourage a balance of time spent active away from devices and time spent using them in a healthy way.

This is especially problematic because children in the age bracket this blog focuses on were not getting enough activity anyway, in a 2019 study of 1.6 million tweens and teens worldwide, the WHO found that “more than 80% of school-going adolescents globally did not meet current recommendations of at least one hour of physical activity per day” (WHO, 2019).

In reporting on their study, the WHO provides the positive news that the United States had one of the three lowest levels of insufficient activity, which they postulize is due to “good physical education in schools, pervasive media coverage of sports, and good availability of sports clubs” (WHO, 2019). Given that two of the three activities listed ceased with the shut down of schools and community activity centers in April 2020, and that they have not been replaced by other options for tweens and teens, it is reasonable to suspect that rates of insufficient activity have increased further in the U.S.

Some believe in a holistic solution to the challenges of creating an environment in which youth maintain their well-being during a time of increased digital use, drawing from disparate fields to ensure that the multi-faceted needs of users are met. A review in Science and Engineering Ethics, observes that effective design through “positive computing” meets user needs by drawing from “requires expertise from diverse fields such as public health, bioethics, sociology, philosophy, psychology, public policy, media studies, literature, and art” (Burr, 2020). The emphasis on inter-disciplinary perspectives when ensuring digital well-being provides may prove more effective when designing user experiences that place well-being at the forefront.

Digital Well-Being Resources

Students would benefit from resources that safeguard children’s (and adult’s) digital well being, and establishing healthy guidelines that children can follow with minimal adult assistance.

England provides examples of guidelines and methods for increasing activity offline and encouraging well-being as youth increase their time in digital environments. A publication by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development includes England’s “Digital 5 A Day (Connect, Be Active, Get Creative, Give, Be Mindful) as a way to encourage youth to use technology in a healthy way and to ensure that it does not take an oversize role in their lives (OECD, 2018).

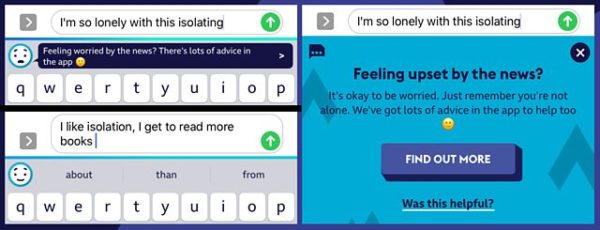

British media offers a tool that may be worth adopting in the United States to support healthy use of digital devices with it’s Own It App. The tools supports children develop healthy habits, maintain safety, and practice mental well-being habits while using devices. Unlike most resources, this audience for the app is youth rather than parents, which is particularly relevant in this time when many students engage in technology use with minimal supervision (European Broadcasting Union, 2020). The app enables the user to record their feelings and “better understand their behavior online and its effect on others, and to navigate the new world safely” (Leonard, 2020).

Digital well-being tools accessible to United States based youth are less intuitive or ingrained in their devices. One example is the suite of wellbeing resources for families at Google. The resources include interviews with researchers and psychologists, an overview of google tools, a guide for users in general during COVID,and recommendations for users (Google, 2020).

Perhaps the strongest tool in the suite for educators is the guide for developers, which addresses the health of users in a more holistic way, with seven “dimensions of wellbeing” that include physical, intellectual, social, environmental, mental, occupational, financial (Google, 2020). As an educator, it is easy for me to forget that occupational and financial well-being challenges affect my tween and teen students, although this may present differently than in adults. For example, food scarcity or homelessness resulting from unemployment or financial challenge in the home affect the wellbeing of my students.

Several non-profit organizations provide digital resilience and digital well-being resources primarily geared to parents and educators. One example comes from Internet Matters, which focuses on digital resilience for children in elementary, middle and high school (Internet Matters, 2020). Another example is Common Sense Media, which has an extensive Coronavirus resource page and an online learning resources at “Wide Open School.”

In Summary

As the months pass and students continue to learn remotely due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a focus on maintaining children’s health and general well-being through mindful, deliberate use of technology grows more essential. We are no longer in the frantic initial phase of remote teaching and learning, and can take the time to examine children’s habits and the ways in which technology tools can improve or diminish their health. Then take steps to improve the children’s well-being in this increased digital environment.

Sources

American Academy of Pediatrics (October 7, 2016). Digital Media and Your Children and Teens: TV, Computers, Smartphones, and Other Screens. HealthyChildren.org. Retrieved from https://healthychildren.org/English/family-life/Media/Pages/Adverse-Effects-of-Television-Commercials.aspx

American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Communications and Media (November 1, 2016). Where we stand screen time. HealthyChildren.org. https://healthychildren.org/English/family-life/Media/Pages/Where-We-Stand-TV-Viewing-Time.aspx

European Broadcasting Union, (April 24, 2020). “Own it” app – BBC. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/H4t1c_f_IYA

Burr, C., Taddeo, M. & Floridi, L. The Ethics of Digital Well-Being: A Thematic Review. Sci Eng Ethics 26, 2313–2343 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-020-00175-8

Council on Communications and Media, (November 1, 2016). Media use in children and adolescents. Pediatrics November 2016, 138 (5); Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2592

Google (2020) Digital wellbeing. Retrieved November 1, 2020 from https://wellbeing.google/

Google (2020) Google digital well being product experience toolkit. Retrieved November 1, 2020 from https://drive.google.com/file/d/1BhlGQ0aUox-HHZ72XDAcOloeClFKv_Ho/view.

Internet Matters. Digital resilience toolkit. Retrieved November 1 2020 from https://www.internetmatters.org/resources/digital-resilience-toolkit/

Leonard, J. (July 30, 2020) Behind the scenes at the BBC’s groundbreaking Own It app. Computing. Retrieved November 1, 2020 from https://www.computing.co.uk/feature/4018405/scenes-bbc-groundbreaking-app

OESCD. (2018) Children and young people’s mental health in the digital age. Retrieved October 31, 2020 from https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Children-and-Young-People-Mental-Health-in-the-Digital-Age.pdf

ParentsTogether Foundation (April 23, 2020). Survey shows parents alarmed as kids’ screen time skyrockets during COVID-19 crisis. Parents-together.org. Retrieved from https://parents-together.org/survey-shows-parents-alarmed-as-kids-screen-time-skyrockets-during-covid-19-crisis/

Vanden Abeele, M. (October 17, 2020). Digital wellbeing as a dynamic construct, Communication Theory. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtaa024

World Health Organization (November 22, 2019). New WHO-led study says majority of adolescents worldwide are not sufficiently physically active, putting their current and future health at risk. Retrieved November 8, 2020 from https://www.who.int/news/item/22-11-2019-new-who-led-study-says-majority-of-adolescents-worldwide-are-not-sufficiently-physically-active-putting-their-current-and-future-health-at-risk