School boards are the consummate example of local control within the structures of a democratic system because board members are elected locally and make decisions regarding local issues, yet their decisions almost universally impact individuals who have the smallest role in board member elections: students. Additionally, school board members infrequently represent the demographics of the school population. In this way, school boards are also a poor example of the way in which democratic institutions hold elected officials responsible for their decisions through the election process. The demographic differences between elected school board officials, the people they serve, and the electorate that chooses them has an impact on educational outcomes for students and mitigating those differences may support greater student achievement for minority students who represent an increasing portion of the student body (National Center for Education Statistics, 2021). Although school boards routinely make decisions impacting minority students, the structure of school board elections results in school boards that do not represent the demographics of the schools they control, and disincentivizes decision-making to benefit minority students.

Today’s school boards have a substantively greater impact regionally than school boards a century ago because the number of independent school districts has shrunk to 10% of its total in 1910 (Kogan & Lavertu, 2021a), which has resulted in two significant changes to the powers of school boards. School board members have decision-making control over a larger number of students and more diverse student demographic groups, and the complexity of governance of individual districts and educational institutions has increased. These changes have increased the important role of school boards in ensuring public school students, including minority students, have access to a quality education and opportunities.

Further, an examination of patterns of achievement gaps in the United states shows that “nearly 90% of the variation in racial achievement gaps is observed within states,” (Kogan & Lavertu, 2021a) which in turn means that local efforts that target the specific educational needs of students in local areas better serve student needs than an overarching, national or state level interventions. Increased reliance on decisions at the school board level has disproportionate impacts on the achievements of minority students. For example, in 2013 California consolidated several programs that benefitted minority students into a single funding source which school districts could allocate with minimal oversight or direction, opening school districts to both praise and lawsuits as they shouldered the responsibility allocating these funds to increase achievement among minority students (Kogan & Lavertu, 2021a; Nittle, 2016). Similar education reform initiatives throughout the United States that grant greater control of local educational institutions have resulted in a need for greater examination of how well the demographic composition of local school board aligns with the demographic composition of the district, and the impact that alignment has on students.

A disparity between the electorate and student population in districts presents one reason that school boards may look very different from the students they serve. Voters in school board elections tend to be significantly whiter than the students on whose behalf they vote, and less likely to have children themselves. Kogan and Lavertu explain that “most of those who cast ballots in school board elections do not have children enrolled in local schools. . . this demographic disconnect is most pronounced in terms of race, with most majority-nonwhite districts having a majority white electorate” (2021a). In the increasing number of districts since 2014 with majority nonwhite student bodies, 60% of the electorate was white, as were 80% of the school board members (Kogan & Lavertu, 2021a). As a result, the electors to which school board members must answer in order to remain in office do not typically reflect the diverse students whose lives are most impacted by the board’s decisions.

While it is difficult to study the direct effects of this disparity, comparing the achievement gap between minority and white students in districts based on the degree to which the school board demographic aligns with the student body provides an indicator of whether election structures decide on school board members truly serve the needs of all students. Kogan and Lavertu’s study draws a direct correlation to this, stating “the achievement gap between white and nonwhite students tends to be larger in districts where the electorate looks most dissimilar from the student population (2021a). Specifically, even a single percentage point of white over-representation in the electorate (verses the student body) is associated with .0005 to .01 standard deviations increase in the achievement gap between white and non-white students in most districts, which is “equivalent to more than half a year of learning” (Kogan & Lavertu, 2021a). Clearly, minority under-representation in the electorate and by extension within the board itself has significant negative repercussions on the educational outcomes for minority students.

Academic Impact of Diverse School Boards

The inverse of Kogan and Lavertu’s findings regarding over-representation of white people in the electorate and school board is also true: school boards that more closely represent the ethnic makeup of school populations positively impact the achievement levels of minority students. The school board does not have to be majority minority for the impact of diversity to be evident, and electing one minority school board member “leads to student achievement gains of approximately 0.1 student-level standard deviations” (Kogan & Lavertu, 2021b). However, these changes do not occur overnight. The 0.1 deviation number referenced above occurs after the sixth year following the election, and most achievement gains begin during the fourth and fifth year following the election that increases the school board’s diversity (Kogan & Lavertu, 2021b). This may be due to changes Kogan found that rose out of the increase in school board diversity, such as increased diversity in school administrations, and an increase in funds from bonds (Kogan & Lavertu, 2021b). One potential reason why the addition of minority representation on school boards decreases these gaps may be that individuals who are members of an underserved community are more aware of the problems that result from that community’s lack of representation in decision making, and therefore notice the greater need for funding and reform.

Darden and Cavendish observe that unfamiliarity with disparities results in their perpetuation, saying “the unfortunate reality is that school boards and superintendents often do not realize these disparities exist within their districts and do not realize that the common practices they employ often are the cause of high-poverty schools having inferior resources” (2012). For example, when California consolidated funding marked for programs disproportionately impacting minority youth into a single fund and allowed school districts leeway in its administration, despite benefits for the overall student population in the state, researchers found that about half of the districts studied “spent less per student on their highest-needs schools on average than on the rest of their schools” (Silberstein & Roza, 2020). Disproportionate allocation of resources and funds among schools within the same district historically has received less attention than funding inequities nationally (Darden & Cavendish, 2012). Yet equity in funding decisions is one issue over which local school boards have direct influence and one which is directly related to the ethnic composition of the school board.

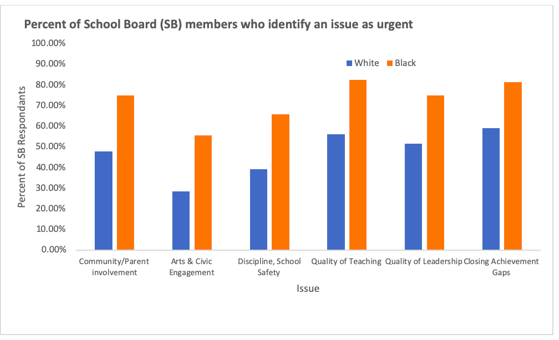

School board member demographics affect the importance that the board gives issues relating to minority students. Minority school board members deem multiple issues related to student achievement more urgent than other school board members (table 1), which may help explain changes that occur when even one member of the school board is a member of an ethnic minority. For example, school board members who identify as at ethnic minorities identify closing achievement gaps as important almost 30% more frequently than their white peers, and the gap is even greater when the school board member is both a minority and female (Blissett & Alsbury, 2018).

Table 1

One Method of Reform

If a disproportionately white electorate results in disproportionately white school boards, which in turn results in achievement gaps remaining for minority students, one solution is to increase turn out among minority voters in school board elections. One method of doing so is to align school board elections with national and state elections because they result in higher voter turnout in general. Doing so has several beneficial outcomes. First, a smaller share of voters in these elections are older or childless (Kogan & Lavertu, 2021a), and more are parents, racially diverse voters, and “highly educated voters” (Allen & Planck, 2005), which in turn means school initiatives on the ballot alongside school board member elections are less likely to fail. Consolidating school elections to occur alongside national or state elections also reduces election costs compared to off-cycle elections (Allen & Planck, 2005). For these reasons, running school board elections at the same time as national and state elections is a viable method of improving turn out among voters more likely to choose a minority candidate.

A common concern about consolidating elections is that the school board election and school issues get lost among the coverage of state and national candidates and issues. However, Allen and Planck show that newspaper coverage of local issues increases dramatically in consolidated elections, from “three or four stories per election,” to “almost daily for 3 weeks prior to the election” (2005), which increases voter awareness and understanding of local issues. When voters have a better understanding of school related candidates and issues, they can make better-informed choices on their ballots.

A second concern occurs when districts have come to rely on off-cycle elections to pass measures that may not be popular because these small elections “provide an opportunity for school district interests to be satisfied” (Allen & Planck, 2005). However, the small turnout sometimes backfires for districts, such as when an unknown or fringe candidate is elected “because they need only garner a small number of votes to win” (Allen & Planck, 2005). Consolidated elections remove the variability that small elections cause because they involve a larger number of voters representing the community demographics more accurately.

In conclusion

While school board members tend to respond to the voters who elected them, because that electorate tends to be whiter and less likely to have children than the families who send their students to public schools, this response is does not benefit many students who are impacted by school board decisions. Kogan observes that under the current system by which we choose them, “school board members face the least political pressure to address persistent racial achievement gaps in precisely the districts where those gaps are largest,” (2021a). Even a small increase in minority representation on school boards results in significant academic improvements for minority students, and an overall increase in bonds and other local measures that benefit all students. The answer to the problem of school board members who do not answer politically to the people whom they serve may be to increase the turnout of minority and parent voters, which in turn applies greater political pressure to boards to ensure that their decisions benefit all students.

References

Allen, A., & Plank, D. N. (2005). School Board Election Structure and Democratic Representation. Educational Policy, 19(3), 510–527. doi:10.1177/0895904805276144

Blissett, R. S. L., & Alsbury, T. L. (2018). Disentangling the Personal Agenda: Identity and School Board Members’ Perceptions of Problems and Solutions. Leadership & Policy in Schools, 17(4), 454–486. https://doi-org.ezproxy.spu.edu/10.1080/15700763.2017.1326142

Darden, E. C., & Cavendish, E. (2011). Achieving Resource Equity Within a Single School District: Erasing the Opportunity Gap By Examining School Board Decisions. Education and Urban Society, 44(1), 61–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124510380912

Kogan, V., Lavertu, S., & Peskowitz, Z. (2021a). How Does Minority Political Representation Affect School District Administration and Student Outcomes? American Journal of Political Science, 65(3), 699–716. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12587

Kogan, V., Lavertu, S., & Peskowitz, Z. (2021b). The Democratic Deficit in U.S. Education Governance. American Political Science Review, 115(3), 1082–1089. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055421000162

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2021, May). COE – Racial/Ethnic Enrollment in Public Schools. Annual Reports and Information Staff (Annual Reports). https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cge

Nittle, N. K. (2016, August 25). The Local Control Funding Formula Is Under Scrutiny in California. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2016/08/will-there-ever-be-a-perfect-way-to-fund-schools/497069/

Silberstein, K., & Roza, M. (2020, November 11). Analysis: California Gives Districts Extra Money for Highest-Needs Students. But It Doesn’t Always Get to the Highest-Needs Schools. The 74. https://www.the74million.org/article/analysis-california-gives-districts-extra-money-for-highest-needs-students-but-it-doesnt-always-get-to-the-highest-needs-schools/