As educational institutions evolve in their approaches to remote crisis learning from the confusing first days of the initial spring shut down to the months after restarting this fall, it is important to pause and reflect on the ways in which our implementation of technology-based distance learning both raises and lowers barriers for underserved populations of learners and their families.

Finding articles and recommendations from reputable sources about the myriad of ways in which online learning has left low income students, minority populations, and students with disabilities is easy. However, digging through them to unearth the data needed to help build a picture on which to reflect often proves frustrating. Specific challenges unique to this pandemic emerge to make data far more difficult to find than headlines might suggest. These challenges center around a lack of current data and the rapid pace of change in education during COVID which results in an over-reliance on think and anecdotes to shape our discussion.

Anecdote and Opinion Fill A Void in Current Data

Anecdotally, as a parent and teacher I see elements of remote learning that lower barriers for students with disabilities and ways in which learning from home provides more effective accommodations for older or more self-directed students with disabilities than face to face learning can provide. Examples from my home and classroom abound:

- A student who is allowed fidgets or attention aids may use them without drawing attention to themselves.

- A child who is allowed to stand, move, or take breaks during instruction can do so without standing out.

- Students who require learning sessions to be broken down into smaller chunks can do this more easily with asynchronous learning than in the classroom.

- Students are able to bring support animals or objects into the learning environment.

- When all children are only using technology tools, the child who uses a screen reader or digital scribing tool does not stand out.

- Google Classroom’s function allowing teachers to assign different work to specific students can make work modifications more subtle than different handouts in the classroom.

- Students can adjust their monitors to meet their vision needs without anyone else seeing.

One might be skeptical of the benefit of using an anecdotal list of one person’s experience when reflecting on the effectiveness of remote-learning. Yet, many of the articles from well-respected publications about the challenges of learning during COVID consist of anecdote, opinion, quotes, and data from before the pandemic.

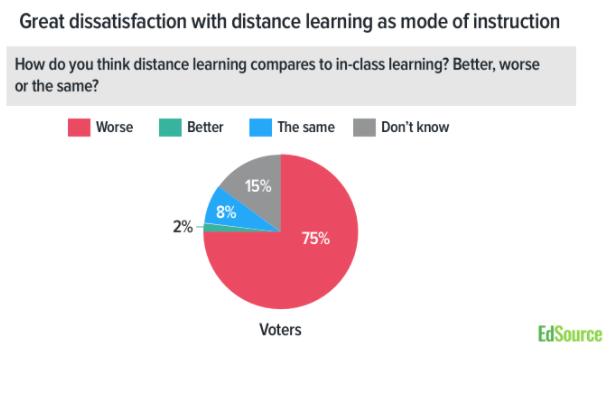

The first results of a google search of news sources within the last month bring up an October 8th article from EDSource, with the worrying title “California voters, including parents, have deep concerns about distance learning” (Freedburg, 2020). The title includes several deeply concerning graphs, including one showing that 75% of voters polled feel that remote learning is worse than in person learning (EdWeek 2020). However, this data is based on a poll of 838 voters in California conducted “between August 29 and September 7th (Freedburg, 2020). Given that California has 20,921,513 registered voters as of July 2020, this study seems small despite its outsize conclusions (California Secretary of State, 2020).

The voters who responded were understandably worried about the state of education but their worry is not the same as hard data about student achievement (or lack thereof), nor is it particularly relevant to current learning given that many districts in California begin the first week of September and were not in school at the time of the survey according to a California website of public holidays (Public Holidays, 2020). This article addresses the limitations the date of the survey causes, saying “The poll was conducted just as distance learning was getting under way, so parents’ views may change as more of them have direct experience with remote instruction for a prolonged period during the coming months” (EdWeek, 2020). While acknowledging the limitations is ethically sound, it does not fill the void we face in data about the effectiveness of our techniques in education this fall.

The remaining articles did little to fill the gap in hard data. TuftsNow published an article on October 12th titled “How COVID-19 Has Affected Special Education Students” that quotes several experts who explain multiple probable problems of remote crisis learning (Nelson, 2020). Their expertise is welcome when considering how to effectively provide inclusive education, but they cannot replace studies or data. This article specifically had zero studies or actual data about the current situation (Nelson, 2020). Neither did “States Facing Challenges as COVID-19 Radically Reshapes Higher Education” from the National Council of State Legislators post on September 23rd, which cites multiple studies to prove the assertion in the headline (Smalley, 2020). However the only studies directly addressing student achievement and access are from 2013, and two from 2018. This is not to say that the article is invalid, simply that it cannot be used to accurately gauge the state of education and access for at-risk populations in education this fall during remote learning.

The Dearth in Data is Understandable

The void in extensive high-quality research on this fall’s educational practice may be ongoing, if the article “Shut Out of Schools Due to Pandemic, Many Education Researchers Say Their Work Is ‘In Shambles’” from September 2020 is accurate (Toppo, 2020). It uses a series of interviews with k-12 education researchers to explain how the pandemic has taken a heavy toll on quality research regarding the ways in which we teach and children learn. Researchers cited lack of access to teachers and students as well as lack of state standardized testing data from last spring as reasons their studies on learning changed or halted.

Projections and Models Fill the Void

The New York Times article “Research Shows Students Falling Months Behind During Virus Disruptions” provides a dire headline that stands on shaky ground, citing a projection by Kuhfeld published in Educational Researcher , statistical models, and several articles (2020). The projection relies on “estimates from prior literature and. . . analyses of typical summer learning patterns of five million students” neither of which is data reflecting the actual experiences of students in spring crisis learning (Kuhfeld, 2020). The statistical model from McKinsey Company predicted that the 3 groups of students they looked would lose educational ground due to access and equity issues. (2020). While there is no reason to question the quality of the projection or statistical modeling, neither source is a study of actual student learning during the spring, and educators need to keep the limitation of that in mind while assessing and planning our crisis-based instruction.

Other citations in this article are less useful as data. They include the New York Times own articles from the start of school closings, such as one from March that it cited to support the assertion that students “are not receiving traditional grades, and some have parents who are working outside the home or who are not tech-savvy, and are unable to assist with online schooling“ (Goldstein, 2020). None of this is surprising, since the articles is from June 6th, 2020, however the New York Times online practice of placing dates for articles at the bottom means that this date is easily missed by casual readers. In the current rapidly-changing education environment, this article is already outdated, yet because articles often bounce around for months as social media users share it, often articles such as this one continue to shamble around the internet long after the situation about which they are written has changed.

The New York Times is not alone, many of the articles I found site rely on anecdotes, old data, and interviews. This is understandable because we are only 1-2 months into the fall school year, so most studies examining student learning loss and access concerns focus on the chaotic spring learning environment rather than the more intentional roll out this fall that followed a summer in which many teachers and administrators engaged in extensive professional development, and in which many state departments of education began providing clearer, more consistent guidance.

Finding Useful, Current Data on Inclusion and Learning During COVID-19

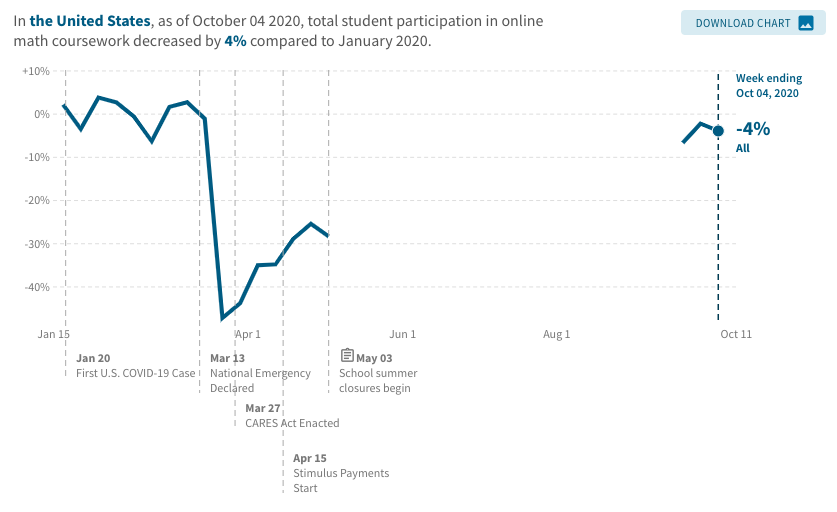

Sources of data on current learning trends is understandably sparse, however Tracktherecovery.org, provides current data regarding a variety of areas, including math education (Opportunity Insights, 2020). The data and charting can help educators draw conclusions regarding the general trend of educational effectiveness among learners of various economic classes. However, the summaries at the top of the charts can miss the context educational institutions need to make solid decisions regarding the efficacy of online learning. For example, The website proclaims “In the United States, as of October 04 2020, total student participation in online math coursework decreased by 4% compared to January 2020” above a graph showing this data (2020). However, the graph also shows that participation is up 2.4% from February 2020, and up 23.5% from its highest point in the spring shutdown. By that measure, educational institutions have made significant progress from those first days.

The graph and data are useful for examining the disparities in the rates by which low income, middle income, and high income students are learning and accessing education (Opportunity Insights, 2020). While gaps remain between these groups, they are significantly smaller than in the spring during that initial scramble, and the rates at which middle income students accessed math education align significantly more closely to that of their low income peers than to that of those students in the high income category (2020). Educators should consider expanding their supports for low income students in math classes to include those struggling whose families are in the middle class.

Solutions from Existing Inclusive Practices

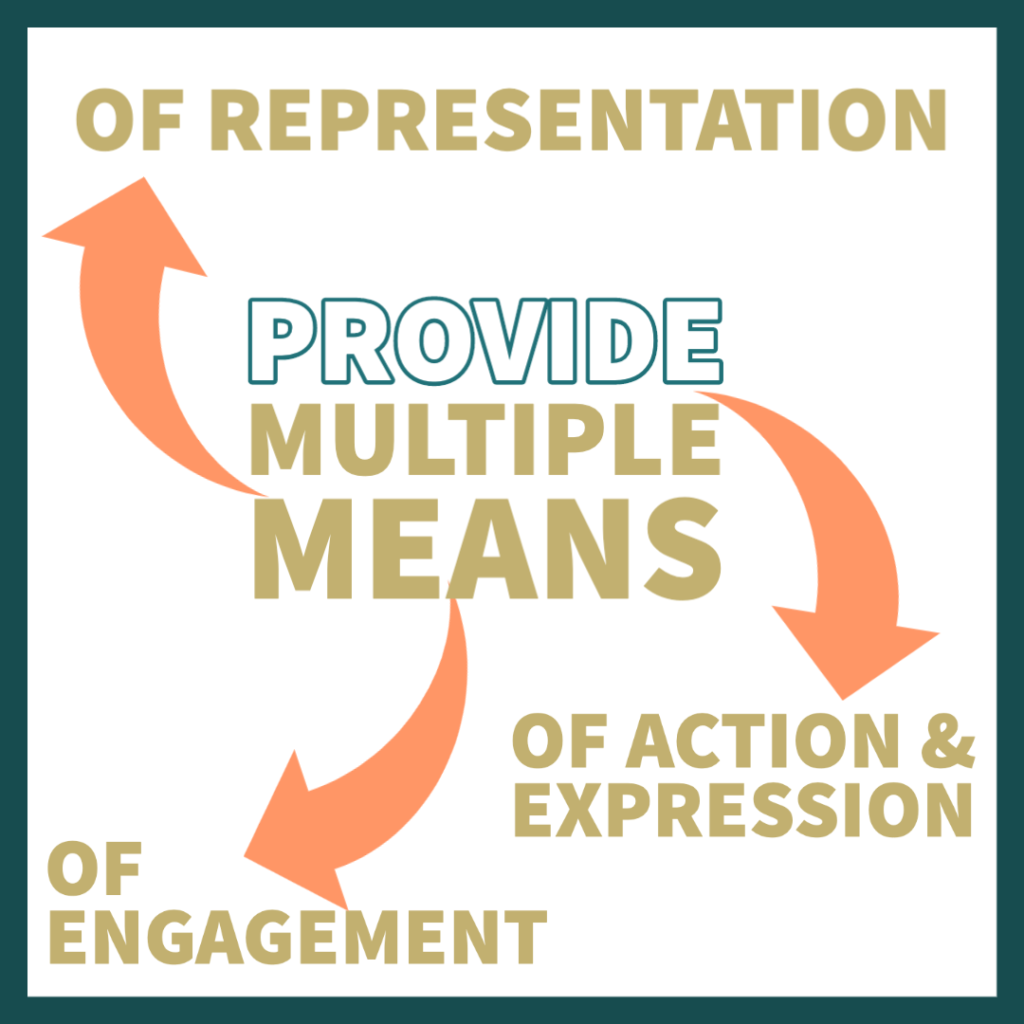

With the lack of solid information regarding the current situation, educators can adapt philosophies and practices that have proven effective in face to face teaching. One such format is Universal Design for Learning, which adapts well to online instruction. UDL is a method of lesson planning and instruction that focuses on ensuring inclusion throughout each step of the process, Alison Posey explains at Understood.org: “UDL guides the design of learning experiences to proactively meet the needs of all learners. When you use UDL, you assume that barriers to learning are in the design of the environment, not in the student” (Posey, 2020).

Ari Flewelling at Ed Tech explains how aspects of UDL transfer well to digital instruction, and provides lists of methods to ensure accessibility based on UDL:

“conduct accessibility checks to ensure platforms and resources used for remote learning are safe for students and integrate with pre-existing systems. Turn on captions as a default for instructional videos. Ensure software or platforms have a text-to-speech option. Be mindful of those and other features that can help students understand and engage with lessons.”

(Flewelling, 2020)

Flewelling explains that UDL requires a mental shift in focus district-wide that emphasizes accessibility and may serve to minimize the gap in learning for this group: “shifting the district lens to thinking about special education first. . . will support educators as they create inclusive spaces, differentiate instruction, and implement inclusive practices that support progress toward meeting the needs of special education student and their peers.” By shifting to prioritize learners with disabilities, we put in place safeguards that more easily catch those learners who are struggling in online education.

ISTE provides suggestions that align with UDL in that they emphasize accessibility with the intent of improving accessibility to learning for all students, including those with disabilities or in underserved populations. For example, ISTE suggests that educators provide multiple means of accessing learning, “give students the option of reading text, watching videos, listening to audio or examining images. . . virtual tours, augmented reality or digital 3D” (2020). By allowing students to choose the best way to access their information, educators can help students develop agency over their own learning as they choose the easiest method for their situation.

One suggestion ISTE provides that is not typically included in UDL, but which adheres to its spirit is prioritizing Open Education Resources. OER resources lower an economic hurdle for students in lower income brackets. It allows them to access materials without paying fees. This is useful on a student-by-student basis at the collegiate level, and schoolwide in k-12 systems, where schools pay for texts assigned to students.

Though the data answering the question of whether technology tools currently work to ensure an inclusive learning environment remains unclear because we are in the midst of teaching in a crisis situation, best practices for inclusion can be adapted for a remote environment.

Sources

California Secretary of State. (2020, July 3). 123 day report of registration [Fact sheet]. California Secretary of State. https://elections.cdn.sos.ca.gov/ror/123day-gen-2020/historical-reg-stats.pdf

Dorn, E., Hancock, B., et al. (2020, June 1). New evidence shows that the shutdowns caused by COVID-19 could exacerbate existing achievement gaps. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and-student-learning-in-the-united-states-the-hurt-could-last-a-lifetime

Flewelling, A. (2020, August 24). When virtual learning barriers collapse, inclusion expands. EdTech Focus on k-12. https://edtechmagazine.com/k12/article/2020/08/when-virtual-learning-barriers-collapse-inclusion-expands

Freedburg, L. (2020, October 8). California voters, including parents, have deep concerns about distance learning. Retrieved from EdSource: https://edsource.org/2020/california-voters-including-parents-have-deep-concerns-about-distance-learning/640685

Goldstein, D. (2020, April 30). Should the virus mean straight a’s for everyone? New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/30/us/coronavirus-high-school-grades.html

Goldstein, D. (2020, June 5). Research shows students falling months behind during virus disruptions. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/05/us/coronavirus-education-lost-learning.html

Indiana University. (2018, September 19). College students have unequal access to reliable technology, study finds. ScienceDaily. Retrieved October 11, 2020 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/09/180919100950.htm

Kuhfeld, M, Soland, J. et al. (2020, May). Projecting the potential impacts of COVID-19 school closures on academic achievement. (EdWorkingPaper: 20-226). Retrieved from Annenberg Institute at Brown University: https://www.edworkingpapers.com/ai20-226

Nelson, A. (2020, September 29). How COVID-19 has affected special education students. TuftsNow. https://now.tufts.edu/articles/how-covid-19-has-affected-special-education-students

Opportunity Insights (2020). Track the recovery. Retrieved from: https://tracktherecovery.org/

Posey, A. Universal design for learning (UDL), a teacher guide. Understood.org. Retrieved October 10, 2020 from: https://www.understood.org/en/school-learning/for-educators/universal-design-for-learning/understanding-universal-design-for-learning

Public Holidays Global. (2020). California school calendar. https://publicholidays.us/school-holidays/california/

Smalley, A. (2020, September 23). States face challenges as COVID-19 radically reshapes higher education. State Legislators Magazine. National Conference of State Legislators: https://www.ncsl.org/bookstore/state-legislatures-magazine/covid-19-brings-new-uncertainty-for-schools-at-all-levels-magazine2020.aspx/

Snelling, J. (2020, March 23). 7 ways to make remote learning accessible for all learners. ISTE. https://www.iste.org/explore/learning-during-covid-19/7-ways-make-remote-learning-accessible-all-students

Toppo, G. (2020, September 22). Shut out of schools due to the pandemic, researchers say their work is ‘in shambles’. The74. https://www.the74million.org/article/shut-out-of-schools-due-to-pandemic-many-education-researchers-say-their-work-is-in-shambles/

Xu, D., Smith Jaggers, S. (2013). Adaptability to online learning: different types of students and academic subject areas. Journal of Higher Education, 85(5). Retrieved from Community College Research Center: https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/adaptability-to-online-learning.html