Every year there seems to be more on our plates: more responsibilities, more students, more challenges, and more expectations. Even as our loads grow, our supports shrink: fewer resources, less training, and less time to meet or plan. As more schools move to inclusion models for students with disabilities, one of those items that is “more” includes expectations surrounding differentiation and inclusion. However, often additional training and time spent with building experts (the special education department in our buildings) is scarce.

For general education teachers, full differentiation and inclusion may seem like an impossible but necessary task. Differentiation is not an onerous additional task. Differentiating as a gen ed teacher with no time is completely possible, but requires some shifts in how we use our time, and in how we think about differentiation.

Make More Time

Before starting to find the time on our own, general education teachers benefit from advocating for more time for planning, prep, and collaboration with special education staff. The National Council for Teacher Quality found that “72% of districts surveyed do not have a specific plan for regular collaboration meetings among teachers (56% do not mention collaboration at all)” (Saenz-Armstrong, 2021). It may feel awkward asking for more planning time, and one way to make it less so is to ask for the time for a specific purpose, such as training from your building experts in differentiation for specific situations. Often, learning specialists have resources available to deploy or methods for streamlining the workload and a one time training meeting can have long-term benefits in the general education classroom.

If you are part of a co-teaching team, the school should provide time for you to meet with your co-teacher. However, if your school is like mine, a shared prep period may be the extent of their ability to provide time. So, when this occurs, it is helpful to plan for a specific time each week to meet with your co-teacher to plan and discuss the classroom. This cuts into other prep time, but in my experience that time is regained through the ways in which improved co-teaching reduces discipline challenges, phone calls home, and discipline paperwork.

Re-Evaluate Priorities

One of the biggest challenges to effectively and efficiently differentiating in the general education classroom is the mindset that differentiation is just another thing teachers need to do. Differentiation exists as an afterthought or add-on to a general education curriculum. When you consider this, it makes sense: general education curriculum is what we are taught to provide, it addresses the standards we teach, and we have been taught that it meets the needs of most kids.

When differentiation is an afterthought, the list of tasks we need to accomplish during our prep period that take priority over differentiation include:

- grading

- lesson planning

- meetings

- family communication

- paperwork

- material creation

- responding to school emails

- using the rest room/eating our lunch

But, in a diverse classroom it is beneficial to re-evaluate prioritizing non-inclusive general education curriculums and build differentiation into our tasks. Differentiation is a part of lesson planning, paperwork, material creation, and even grading. Building in time to differentiate during those tasks instead of seeing differentiating materials as an isolated task makes differentiating easier to accomplish. For example, when creating materials, making a shortened version, an ESL version, or a version for visually impaired students is easiest if you do so during the time you’ve allotted for material creation because it is a few minutes of additional work.

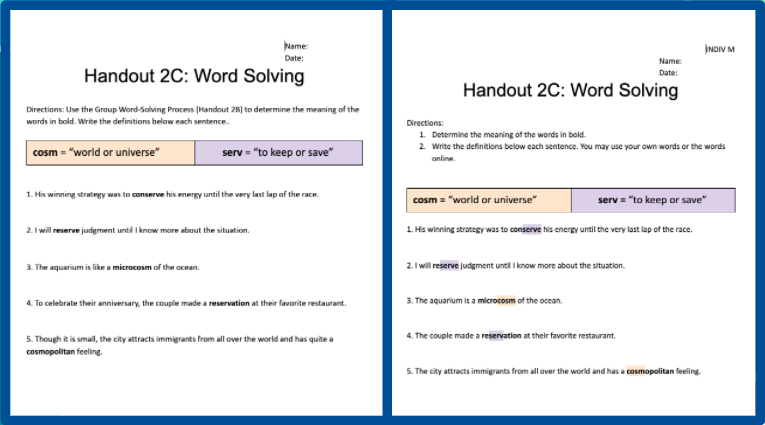

The images below show an example of differentiated vocabulary worksheet that takes very little time to create if you do so immediately after creating the non-inclusive material. The differentiated handout is different because the instructions are numbered steps, which supports students with executive functioning challenges, and the example sentences include answer words that are color coded to match the definitions in the table. Other differentiations that are easier to accomplish while building materials than they are afterward are: shortened assignments, font size changes, and simplified English materials.

Build a Flexible, Self-Sustaining Classroom

One of my favorite examples of a self-sustaining classroom occurred when I was absent while teaching 7th grade. I was sent to the hospital midway through a school day — and had not had time to return to my room or lock my classroom door. The school was unable to find coverage right away, which was especially worrying when security went out looking for my students and could not find them in the halls or fields. Eventually, they went into my classroom and found the entire class – working on their assignments or reading because they’d finished. Not all of my classes would have been so responsible, but this class was able to function entirely without me for a day because they had been empowered to be independent, and because the classroom itself was set up in a way that allowed them to be independent.

Some areas in which you can increase student independence are:

- Placing accessibility tools, such as headphones, fidgets, whisper phones, and other devices on hooks for students to access them independently

- Training students to lead technology check out and check in systems

- Providing a weekly and daily calendar that includes entry tasks for the week

- Posting and maintaining class routines using anchor charts and visual schedules

- Using a sign-in/sign-out method for classroom departures

- Creating a classroom supply area students maintain that includes extra copies of materials

- Minimizing displays that require frequent updating (calendars, etc).

- Allowing students independence in flexible grouping and transitions between groups or activities

- Teaching students to leave their seats discretely to get needed supplies during class.

Setting up your classroom so that students are able to independently engage with most of the room is one way to decrease the amount of on-stage time you spend, allowing you to differentiate on the fly or to engage in activities you might normally do at home during class. For example, instead of grading papers and providing written feedback at home, you can conduct writing conferences during the period. Another way to create additional time for differentiation is to reduce discipline problems and class disruption, both of which can be mitigated through classroom design changes to include flexible seating.

Flexible seating allows you to meet the needs of neurodiverse and neurotypical students better and helps students stay on task and in the classroom. For example, a student may have frequent breaks built into their 504 plan or IEP. However, when those breaks are due to a need to move their body in order to focus a wobble stool, rocking chair or standing desk can decrease the time spent on breaks out of the classroom. These tools can also reduce the number of blurt outs or distracting behaviors. Examples of flexible tools that typically pass fire marshal approval: floor desks, stools, wobble stools, any upholstered furniture that comes from the school itself (ask the custodian what’s in storage), hard back spinning, rolling or rocking chairs, and inflatable poufs.

What’s not in your classroom can be as beneficial as what you’ve added. For example, decorations that wave, dangle, or spin can be immensely distracting, reducing the duration students can stay on task. Excessive decorations and thematic puns can be visually challenging and confusing for some students, as can visual clutter. Taking a careful look through your classroom design and culling anything that pulls attention away from where you need it to be is a way to reduce off-task, distracted time.

Rethink Classroom Management

Many staples of teaching and behavior management can also result in extensive addition to planning time needs. Look through your systems for managing behavior and academics. If something does not serve a purpose or takes additional time with minimal rewards, rethink it.

Below are several examples of classroom management tools I have removed from my classroom that have resulted in a time saving:

- “Potty Passes”

- Class Economy

- Behavior Charts and apps

- Prize Boxes

- Calendar/Seasonal Bulletin boards

- Student Job Rotation

- Word Walls

- Mailboxes

Revise Grading Procedures

There are three primary ways that I have revised my approach grades:

- I do not grade homework anymore (as a middle school teacher)

- I have changed how I handle late work

- I provide frequent feedback and infrequent grades

There are two reasons in addition to time constraints that I no longer grade homework as a middle school teacher: first, homework is of minimal benefit and second, homework is classist. Homework in elementary school has nearly no impact on learning, but that impact gradually increases as students get older starting in 7th grade so experts recommend following the 10 Minute Rule in which “teachers add 10 minutes of homework as students progress one grade” (Duke Today, 2006). This guideline means that 7th graders should have no more than 70 minutes of homework, however that time is divided among all their classes and works out to no more than 15minutes per academic class. Therefore, I do not give homework to 6th graders, and rarely give homework to 7th and 8th graders.

A rising group of evidence and expert opinion agrees that homework is classist, and I’ve gone from firmly believing that homework teaches academic and non-academic skills to understanding that it favors children from households with higher incomes and can result in mispractice when adults in the home cannot provide supervision and guidance. A 2015 study showed that among parents who did not substantively help their children with homework personally, “working-class parents were more likely to point to their lack of knowledge or skill, while middle-class parents can pay for tutors when they do not understand the homework themselves,” which highlights a disparity that results in middle class children having help on homework whether their parents understood the work or not, while working class children only had help when parents understood the work (Lutz, 2015). Homework has the benefit of allowing for reflection and practice, but grading it is unfair and inaccurate because home learning environments vary so wildly. While one child may have a quiet space and adults who can help them with their homework or do it for them, another may be caring for younger children in a noisy home with no adult support while trying to work on the homework. Grading students as if they have equal environments is unfair, even if it is simply on completion.

My late work policy has significantly reduced the time I spend grading and has increased the accuracy of my grades. Previously I excepted student work late at a point reduction, and eventually no longer excepted work after one month. However this resulted in greater work because I needed to maintain a late work van and track how late student work was turned in. Now, I accept work up to two weeks after the deadline but do not reduce the academic grade for that work. As a result, I do not have to track how late the work is nor do I have to figure out how much the point is lowered. This has increased the accuracy of my academic grades because they reflect accurately whether or not the child has met the academic standard. I assess responsibility separately, and students automatically get a level one for late or missing work and a level three for work that is turned in on time. That was me to enter my responsibility grades at the same time that I enter my academic grades and not have to return to them and revise them.

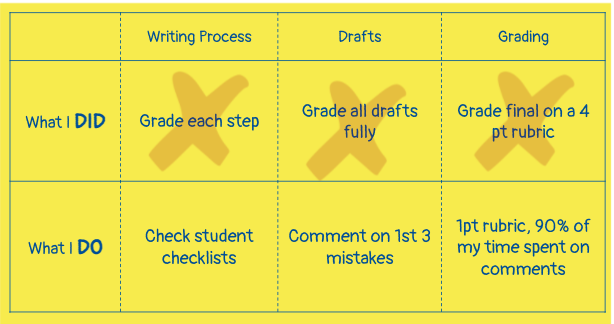

My policy of frequent feedback and infrequent grades may be specific to Language Arts and English classes. Studies conflict on whether or not feedback or grades are more useful in helping students develop writing skills (Gurskey, 2019). When there is no clear advantage to either method of helping students understand where their skills are, it is up to the teacher to choose based on their specific students and experience. I choose feedback because I can provide feedback in writing conferences during class, and because the students in my classes respond well to specific feedback. I frequently give feedback multiple times before grading student writing, which cuts down the amount of grades I enter into the electronic grade book by 3/4. Using this method allows me to spend my time focused on talking with students about their work rather than entering grades.

Choose Technology Tools Wisely

With the mass movement to remote learning of 2020, educational technology companies have had to ramp up the inclusion elements of their technology. Many districts do not allow teachers to use tools that are not ADA compliant, so many tools have accessibility measures. Choosing technology wisely for inclusion requires teachers to look beyond the advertising and examine the usefulness of the tools. One example exists in the form of using the Google document suites with their grading options that allow for a comment bank, a general, placement location, and tracking progress. Microsoft Word offers most of the same tools but because some children may not have Microsoft office on their computers at home it is slightly less accessible.

Other technology tools are useful because they allow for greater engagement with the materials. For example, I prefer to use Loom for giving video feedback to my students over screencastify. This is because Lum includes options such as allowing students to react and showing those reactions at the point in the video where the student reacted, and timestamps for comments that indicated when in the video the student is asking the question or making the comment. This lets me quickly see what is confusing to them or what they’re talking about in their comment. Loom has recently added the option of recording video responses which makes it similar to social media and allows an asynchronous writers conference to feel more immediate. These three options are useful for students with disabilities because they require less executive functioning and they allow students to get the feedback they need through different mediums such as a video a text or even audio.

There are several sources for apps and games that allow students to review information they have learned in class. Typically, review games and sites work on a simple trivia model which allows students to see what they’ve gotten correct or what they’ve gotten incorrect and introduces a level of gamification. However no matter how fancy straightforward trivia games are, they can be difficult for some students so teachers would benefit from being careful in choosing them. For example games that default to flashy images and loud noises require students to turn those options off and that requires some training of students. Games that are strict trivia games like Kahoot do not allow students opportunities to practice in a single setting when they do not have the content knowledge to succeed.

Finally, choosing inclusive ways to share information with families allows you to spend less time on small communications. For example my class agenda is a Google slide that I have made public I’ve been in bedded in my class website allowing parents to access it from their phones. This reduces greatly did amount of parent communication I get asking what students did in class. I have also embedded the calendars from each of my google classrooms into the class website so parents can see when assignments are due. Both of these are one-time tasks because the agenda and calendars automatically update on the class website, which is formatted to be easily read on a mobile device.

Resources

Duke Today Staff. (2006, March 7). Duke Study: Homework Helps Students Succeed in School, As Long as There Isn’t Too Much. Duke Today. https://today.duke.edu/2006/03/homework.html

Guskey, T. R. (2020, October 12). Grades versus comments: Research on student feedback. Kappanonline.Org. https://kappanonline.org/grades-versus-comments-research-student-feedback-guskey/

Lutz, Amy and Lakshmi Jayaram. 2015. “Getting the Homework Done: Social Class and Parents’ Relationship to Homework” International Journal of Education and Social Sciences 2(6): 73-84. Retrieved from https://surface.syr.edu/soc/9/

Saenz-Armstrong, P. (2021, October 6). A look at districts’ planning and collaboration policies for their teachers. National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ). https://www.nctq.org/blog/A-look-at-districts-planning-and-collaboration-policies-for-their-teachers