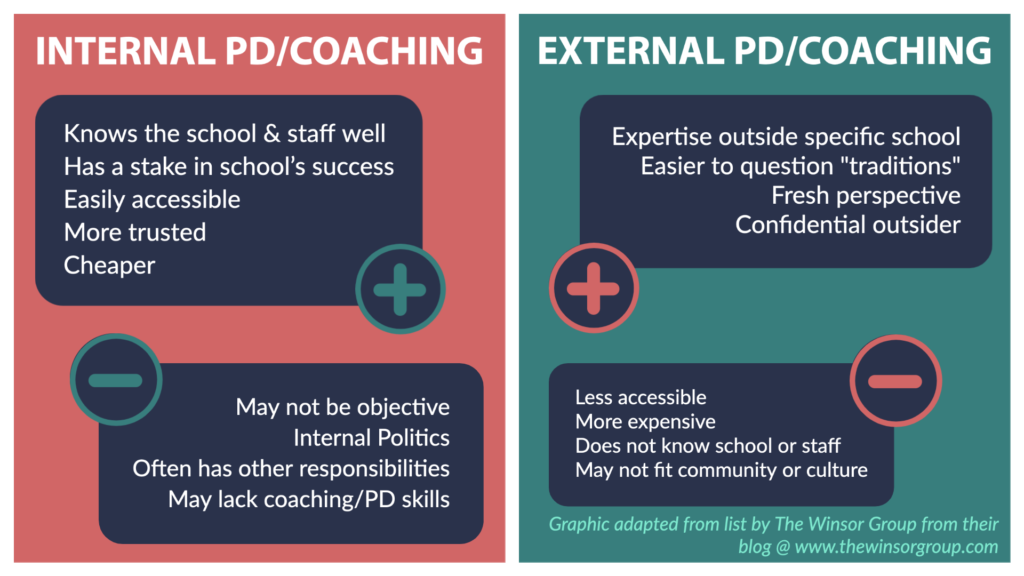

As schools balance the need for ongoing teacher education with the time and monetary costs of professional development, it is important to ask questions about evidence based best practices in teacher training. One such question that impacts decisions administrators make about teacher training is whether it is best to use experts from within the district to conduct trainings or to use outside experts. The answer to that question turns out to be that it doesn’t really matter very much whether the expert providing teacher training is from inside the district or not.

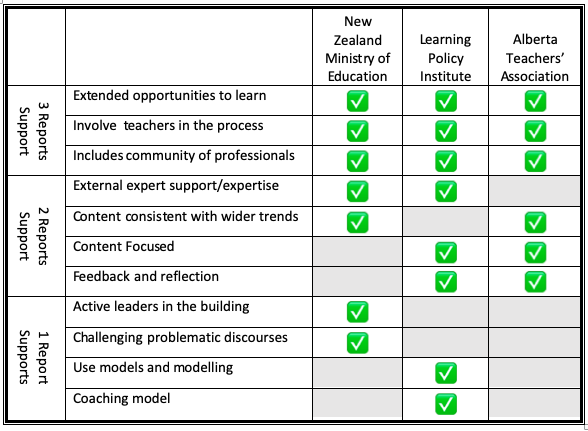

While there are several studies about the manner in which professional development sessions are conducted, the data is limited regarding the efficacy of internal or external trainers. Typically the emphasis is on type and frequency of training, so studies do not differentiate between in-house experts and external professionals. A 2017 meta study from the Learning Policy Institute provides an example of this in its definition of PD expert: “Individuals with a variety of backgrounds can fill the role of expert; in the reviewed studies, coaches and other experts ranged from specially trained master teachers and instructional leaders to researchers and university faculty” (Darling-Hammand, 2017). Further, evidence from several studies found that the presence of “external experts are both positive and negative” because while many programs that had no impact involved internal experts, “most programmes [sic] that had no or low impact also involved external experts” (Timperley, 2007). Finally, an extensive study examining teacher coaching programs concluded “we find little difference in the effectiveness of coaching programs delivered online versus face to face” (Kraft). This suggests that the type of professional development is more important than whether the person who provides it is local or an outside expert.

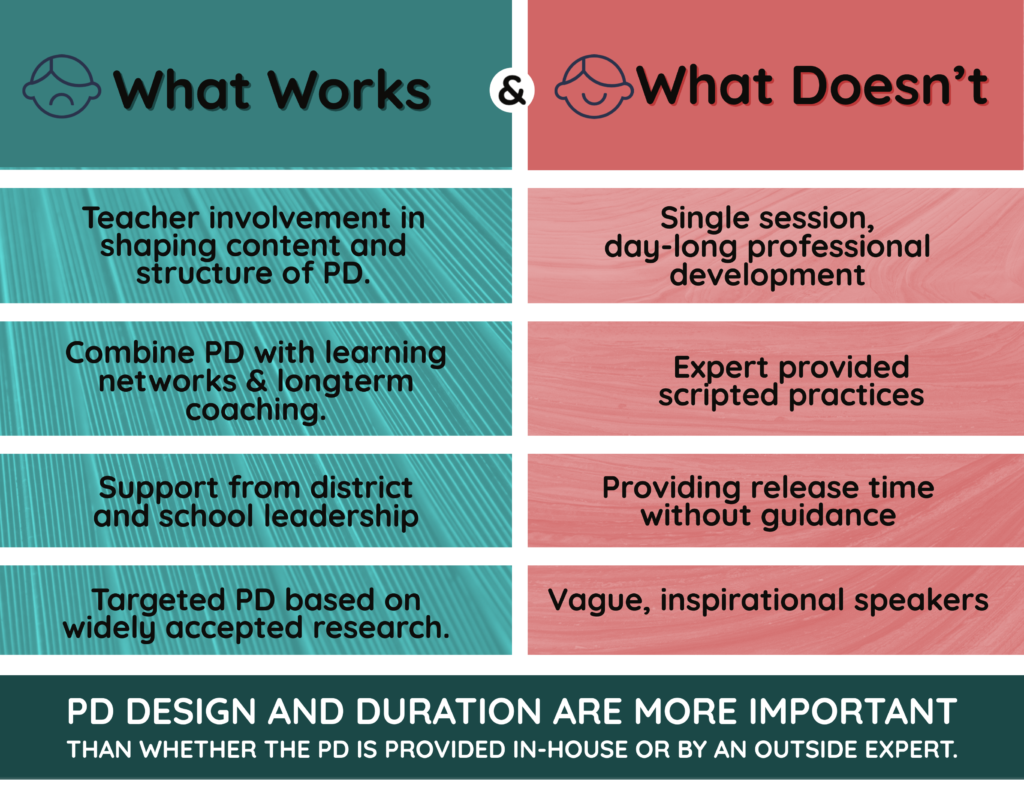

Despite the mixed results of studies regarding experts in teacher training, we can draw important conclusions regarding what does and does not work, which impact the role of both internal and external coaches in teacher professional development.

What Doesn’t Work

Traditional Professional Development doesn’t work. Fourteen years ago, researchers at the New Zealand Ministry of education observed that “PD has been dominated by daylong seminars that took teachers out of the classroom and delivered the same tips and tricks to an entire department, grade level, or school” (Timperlay, 2007). The New Zealand researchers continue by explaining that research consistently shows that “listening to inspring speakers or attending one-off workshops rarely changes teacher practice sufficiently to impact student outcomes,” yet in the United States, this remains the primary form of professional development (Timperlay, 2007).

Single session professional development is known to be less effective in changing teachers’ practices. One meta study states that research indicates that “the traditional episodic and fragmented approach to PD does not afford the time necessary for learning that is “rigorous” and “cumulative” (Darling-Hammand, 2017). As a second blow against professional development of this type, other studies show that if the goal is district-wide change, professional development just doesn’t work, “rigorous studies find that PD programs more often than not fail to produce systematic changes in teachers’ instructional practice, much less improvements in student achievement” (Kraft). This means that not only is the traditional day-long teacher inservice prior to school starting is not as effective as a coaching model of professional development, but it may not be effective in meeting the district’s goals at all. The solution to this dilemma is to match PD plans with district goals (and re-assess if the goal is systemic change), and to move to a coaching model for specific departmental improvements. For budget-conscious schools, moving away from the single-session PD could be cost prohibitive if it entails hiring outside experts for multi month or year coaching commitments.

Expert provided scripted practices don’t work. The New Zealand Ministry of Education report finds that “providers who trained teachers to implement a defined set of preferred practices rarely had a sustained impact on student outcomes” (Timperley, 2007). These scripted or narrowly defined practices may be evidence based, or best practices based on the experts experiences, but they do not allow for the diverse cultures in our schools and communities. In schools, as in business external providers’ “recommendations may not fit internal capabilities or resources” (Windsor Group, 2021). These solutions require strict adherence from teachers implementing them, which is unsustainable and ignores the expertise of teachers. Any benefits seen initially in these narrowly defined methods disappear fairly quickly because teaching requires both planning and responsive to the needs of each class and the moments within the classroom.

Providing Release time without classroom resources or guidance doesn’t work. While expert-created, carefully prescribed solutions do not work, neither does removing the expert from training completely. In examining the results of sixty studies, “there did not appear to be a relationship between funding for release time and impact on student outcomes” (Timperley, 2007). It is clear that simply finding time for teachers to engage in self-study was not adequate to cause improvement in student learning. Vague goals or professional development without adequate instruction is listed as one of the barriers to effective PD on the Learning Policy Research report (Darling-Hammand, 2017).

What Works

External experts working alongside teachers in discussion and learning works. The New Zealand Ministry of Education compares ineffective and effective use of external professional development experts, saying that “external experts who expected teachers to implement their preferred practices were typically less effective than those who worked with teachers in more iterative ways, involving them in discussion and the development of meaning for their classroom contexts” (Timperley, 2007). This focus on teacher engagement and collaboration in the structure and content of professional development aligns with what we know about knowledge acquisition in students: that engaging in the higher level thinking skills of discussion and creation are two of the best ways to cement new learning.

This best practice that appears in multiple sources as a way for coaches and PD leaders to succeed. The Alberta Teachers’ Association suggests that experts providing professional development “invite teachers to collaboratively outline the professional learning they need to become better teachers and . . .build opportunities for professional development/professional learning around sharing curriculum ideas and best practices, co-creating and sharing learning and teaching resources” (Beauchamp, 2014).

Professional Development combined with and learning networks have shown success. Teachers are more successful in acquiring and implementing new teaching methods and skills when they have an extensive learning community to meet with and to engage in discussions with over time. When these communities exist beyond the building or district, they have there are positive effects on teacher perspectives about the training and on student improvement (Darling-Hammand, 2017). Experts facilitating teacher professional development should “provide time and space for collaborative professional learning activities to build collective (school-level) efficacy” (Beauchamp, 2014). These collaborative opportunities and networks can include in-person meetings in school buildings, virtual groups, and social networks online.

The coaching model works well over time in many circumstances. Every source recommended that professional development for teachers include “extended timeframes and frequent contact. . . because, in most core studies, the process of changing teaching practice involved substantive new learning that, at times, challenged existing beliefs, values, and/or the understandings that underpinned that practice” (Timperley, 2007). Changing perspectives and practices over time makes them more likely to be sustainable, and doing so with frequent check ins from an expert coach encourages new skill acquisition.

Targeted PD that aligns to wider trends is typically effective. Professional development that is targeted to specific content or groups is more effective than vague widely focused training. For example, when professional development sessions must be short or can only be a single session, narrowly targeted topics have shown success in raising student achievement” (Timperley, 2007). Additionally, even when professional development stretches over several sessions, best practices include targeting specific, narrowly defined groups, such as departments, or cohorts based on teaching experience because these groups have differing needs. For example, “beginning

teachers and experienced teachers have different professional learning needs; [and] single-subject–area teachers (eg, second language) desire collaboration with other single-subject–area

teachers” (Beauchamp, 2014).

Professional Development based on widely effective research works. Because there is a great deal of evidence about teacher training formats, some of it is contradictory. This allows professional development providers to use data to back their methods even if those methods are less successful than others. The New Zealand Ministry of Education review of studies found that, while most trainings were based on research, the research on which the least effective ones were based “was typically not of the kind that had survived the rigours of adoption by a policy or professional body or was part of a wider programme of research” (Timperley, 2007). As a result, the best professional development relies on data that has been critically assessed and widely accepted.

Support from in-house experts and school leadership for continued development is helpful. Whether or not the initial professional development is conducted by an in-house trainer or by an external expert, buy-in from building and district leaders is essential. Administrators are effective when they support their staff’s growth and development across a spectrum of perspectives, and “their activities were consistent with a number of theoretical perspectives on leadership, rather than one particular perspective” (Timperley, 2007). These in-house experts include administrators, literacy coaches, and department heads, and their effectiveness increased if they are well trained then lead coaching relationships. Best practices mandate that these coaching models be “school-based, sustained over time and part of a coherent school reform model” (Beauchamp, 2014).

School leadership can be defined as master teachers and colleagues as well as administrators and people in official leadership roles. One source examined studies of successfull professional development programs from various countries and found that “system-level leaders” were associated with increases in the effectiveness of teacher training programs (Jensen, 2016). This suggests that the support of key individuals within the school for the ideas presented in the professional development creates a culture in which those ideas are more likely to be successful.

Ultimately, when examining the difference between high-impact professional development and low-impact professional development it is less important who provides the PD than how the PD is structured and supported. Whether a school chooses an outside expert to deliver the professional development or uses in-house expertise, the development is more likely to be effective if it includes the best practices listed above.

Resources

Beauchamp, L., Klassen, R., Parsons, J., Durksen, T., & Taylor, L. (2014, January). Exploring the Development of Teacher Efficacy Through Professional Learning Experiences. The Alberta Teachers’ Association. https://www.teachers.ab.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/ATA/Publications/Professional-Development/PD-86-29%20teacher%20efficacy%20final%20report%20SM.pdf

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M., & Gardner, M. (2017, June). Effective Teacher Professional Development. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Effective_Teacher_Professional_Development_REPORT.pdf

Giordano, K., Eastin, S., Calcagno, B., Wilhelm, S., & Gil, A. (2020). Examining the effects of internal versus external coaching on preschool teachers’ implementation of a framework of evidence-based social-emotional practices. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2020.1782545

Jensen, B., Sonnemann, J., Roberts-Hall, K., & Hunter, A. (2016). Beyond PD Teacher Professional Learning in High-Performing Systems. National Center on Education and the Economy. https://www.ncee.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/BeyondPDWeb.pdf

Kraft, M. A. (2020, July 16). Taking Teacher Coaching To Scale. Education Next. https://www.educationnext.org/taking-teacher-coaching-to-scale-can-personalized-training-become-standard-practice/

McDermott, M., Levenson, A., & Newton, S. (2007). What Coaching Can and Cannot Do for Your Organization. Human Resource Planning, 30(2), 30–37. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.spu.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip&db=bth&AN=25601264&site=ehost-live

Timperley, H., Wilson, A., Barrar, H., New Zealand. Ministry of Education, & University of Auckland. (2007). Teacher Professional Learning and Development: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration [BES]. Ministry of Education. https://www.oecd.org/education/school/48727127.pdf

Hi Deanna, thank you for putting together this insightful post and laying out a clear and balanced comparison on what does and does not work when it comes to internal vs. external coaching. What stood out to me in your post was the finding that “Single session professional development is known to be less effective in changing teachers’ practices”. This really made me think twice in my professional development planning for my teachers. Thank you!

Deanna,

I appreciate your direct writing style and clear formatting used to explain what works and what doesn’t work regarding professional development linked to improving student outcomes. The PD + learning networks + long term coaching model provided makes complete sense! I wonder why the day-long inspirational workshop model is still widely implemented when research contradicts its effectiveness? Excellent post!

Hi Deanna, I really enjoyed your conclusions as a result from a challengingly limited bank of academic research around your question. Your question itself is extremely engaging and is a question I’m sure any administrator has had to weigh. I really like how your solution evolved into clearly outlining what does and doesn’t work. Each of your points for this section was very compelling. I also loved your integration of visuals in this particular post. The visuals really highlight key information for understanding. I wonder how your exploration and answers to your question will impact your building’s PD in the upcoming school years. Thank you for sharing!